Singapore is renowned for its highly structured approach to population management, a hallmark of its nation-building strategy. Over the years, government policies have swung between reducing high birth rates in the early days of independence to encouraging births as fertility rates dwindled. One particularly bold and infamous initiative was the Graduate Mother’s Scheme, introduced in 1984. Though short-lived, this policy serves as a fascinating case study on how Singapore balanced its demographic goals with societal values.

The Historical Background of Family Planning in Singapore

Singapore’s approach to family planning has evolved significantly over the decades. The government’s population policies have been driven by economic necessity and concerns about the country’s long-term viability.

Lee Kuan Yew’s Personal Beliefs

Premier Lee returned to a favorite theme, i.e., the importance of the quality of human material that has sustained Singapore’s impressive economic growth.’ Coupled with his firm belief in the innate (indeed, hereditary) character of those qualities making for this success, eugenic considerations had been for quite a while an important factor in major areas of social policy in Singapore.

Lee had been utterly explicit about his uncompromising elitism and his conviction that the fate of Singapore rested with an elite group of “no more than 5%” who were “more than ordinarily endowed physically and mentally”

[C.K. Chan, 1985] doi: 10.2190/88FW-HNPW-EXP0-3CQK http://baywood.com/

Singapore’s Demographic Challenge: The Need for Policy Intervention

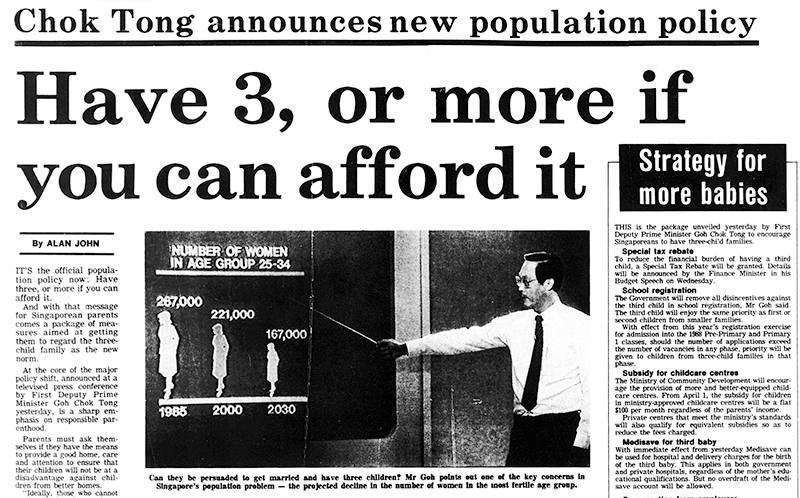

By the 1970s, Singapore faced a demographic paradox. Its post-independence years saw rapid growth in population, but by the time the 1980s rolled in, birth rates began to decline.

Policymakers were concerned about the long-term economic effects of an aging population and a shrinking talent pool. Declining fertility rates created a ripple effect with broad economic and social implications, from a reduced labor force to increased healthcare costs for an aging population.

Initial Family Planning Policies and the Transition to Pro-Natalist Measures

In the 1960s and 1970s, Singapore launched aggressive family planning initiatives like the “Stop at Two” campaign to curb high birth rates. These policies used tax penalties and disincentives to discourage large families. However, as fertility declined to below replacement levels in the late 1970s, Singapore’s approach flipped to pro-natalist measures, attempting to encourage selective childcare, especially among highly educated women.

Key Features of the Graduate Mother’s Scheme

The Graduate Mother’s Scheme, introduced in 1984, stood out because it tied incentives directly to the educational qualifications of mothers. This policy aimed to increase the birth rate among university-educated women under the belief that their children would form a “valuable human capital.”

Incentives for University-Educated Mothers

Under the scheme, university-educated mothers with three or more children received preferential access to better schools for their kids, along with financial benefits. These included subsidized childcare and tax reliefs. This controversial move highlighted the government’s belief in “quality over quantity” when it came to population growth.

Policy Objectives and Justifications

The policy was justified on the grounds of reversing Singapore’s lower fertility rates in educated demographics. The rationale was clear: higher-educated parents would likely nurture children who could contribute significantly to the country’s workforce and economic development.

The Controversy and Public Reaction to the Scheme

The rollout of the Graduate Mother’s Scheme sparked widespread public backlash. Critics questioned the policy’s fairness, equity, and even its overall necessity.

Criticisms of Social Inequality

Public sentiment reflected strong disapproval of the socio-economic bias in the scheme. By prioritizing one demographic group, the government risked alienating the majority of Singaporeans who felt overlooked. Many pointed out that the scheme widened socioeconomic gaps at a time when national unity was critical. The policy seemed to imply that children born to less-educated parents were less worthy of investment—a perspective that ruffled feathers across society.

Impact on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality

Beyond social inequities, the scheme also raised concerns about its implications for gender equality. People debated whether the policy reduced women to their reproductive potential, particularly educated women. The controversy spurred conversations about women’s roles in modern Singaporean society and inspired activism focused on gender equality.

Legacy and Lessons from the Graduate Mother’s Scheme

The Graduate Mother’s Scheme was eventually abolished in 1985, lasting barely a year due to its unpopularity. However, its short tenure left a lasting impact on Singapore’s family policies.

Policy Outcomes and Effectiveness

Despite its ambitious goals, the scheme failed to move the needle on fertility rates among highly educated women. The backlash and lack of broad-based support rendered it ineffective. Policymakers concluded that demographic goals needed to be achieved in ways that fostered solidarity rather than division.

Influence on Subsequent Family Policies

Although the scheme itself was scrapped, it influenced subsequent population policies. Future measures like the “Marriage and Parenthood Package,” Baby Bonus Scheme, and enhanced paternity leave sought a more inclusive approach. These policies offered financial support, tax benefits, and childcare subsidies to families across all income levels, emphasizing fairness and social cohesion while aiming to boost birth rates.

Conclusion

The Graduate Mother’s Scheme stands out as a bold but divisive chapter in Singapore’s history. While it highlighted the country’s willingness to tackle demographic challenges head-on, its exclusionary nature served as a cautionary tale. Policies aimed at population growth work best when they balance economic goals with societal values, respecting the diversity of citizens’ needs and their contributions. Today, Singapore’s approach to family planning reflects a more balanced, inclusive framework—one still rooted in the lessons of its past.