In this blog post, I will review all Minority Oppositions parties. As they are not worth of a full blog post, they will all remain here. To be reviewed. Just to note to all Singaporeans. If any of these political parties stand to contest in your GRC, it is not wise to vote for them, nothing good will come from them.

These parties provide not much substantive alternative solutions other than just hating the People’s Action Party for the sake of hating them

These groups of individuals forming individual small parties are likely to be one of the biggest embaresments of Singapore. A walking bunch of bafoons.

Peoples Power Party : Goh Meng Seng

Please stay out of Politics. His entire party is his ego booster with a bunch of other individuals with not much to show for. Please stay out of politics. This is not American politics where we care about cultural issues. The stint about running against LGBT Candidate was rather, short sighted political move. People care more about bread and butter issues. Please just stay in your job and move on. Save your deposit.

Reform Party : Shadow of Former Glory

The Reform Party (RP) once carried the weight of great expectations. Founded by J.B. Jeyaretnam in 2008, the party was seen as a potential torchbearer of his political legacy—one that challenged the People’s Action Party (PAP) with sharp rhetoric and an uncompromising stance on civil liberties and democratic freedoms. Yet, more than a decade later, the RP finds itself in political obscurity, a shadow of its former glory.

After J.B. Jeyaretnam’s passing, his son Kenneth Jeyaretnam took over the party, but rather than building on his father’s formidable reputation, he has struggled to define RP’s place in Singapore’s opposition landscape. While Kenneth has maintained an outspoken presence online, often critiquing government policies and financial matters, the party itself has failed to gain significant traction. It lacks a strong grassroots base, has not won a single parliamentary seat, and its electoral performances have been lackluster.

The 2011 General Election was arguably RP’s best shot at establishing itself, contesting in West Coast GRC and engaging in a spirited campaign. However, it fell short. Subsequent elections saw diminishing influence, with the party becoming more of a fringe presence than a serious contender. Unlike the Workers’ Party or even the Progress Singapore Party, RP has not been able to sustain a coherent or appealing political platform.

Today, the Reform Party exists more in name than in impact. Its once-promising legacy has faded, and unless it finds a way to reinvent itself and engage voters meaningfully, it risks being remembered as little more than a relic of Singapore’s opposition history—a shadow of former glory.

National Solidarity Party : The Definition of Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result

The National Solidarity Party (NSP) has been a familiar yet perplexing presence in Singapore’s opposition landscape. Despite decades of contesting elections, the party has failed to secure a breakthrough, often running on a platform that lacks distinctiveness compared to its competitors. This raises the question: is the NSP trapped in the very definition of insanity—doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result?

To be fair, Singapore’s political environment is an uphill battle for any opposition party. The People’s Action Party (PAP) dominates the electoral system, leveraging structural advantages and a well-oiled political machinery. But where parties like the Workers’ Party (WP) have adapted, refined their messaging, and built strongholds in Hougang and Aljunied, the NSP has remained stagnant. It has contested across multiple constituencies, yet failed to establish a solid voter base, often appearing as an afterthought in elections.

One key issue is its lack of a compelling political identity. Unlike the WP’s pragmatism or the Progress Singapore Party’s (PSP) focus on middle-ground voters disillusioned with the PAP, the NSP has struggled to carve out a unique space. Its electoral strategy often appears reactive rather than proactive, jumping into contests without a clear long-term vision. The result? A series of dismal performances, candidate turnover, and an inability to build lasting momentum.

If the NSP wants a different result, it needs to break free from this cycle. It must either redefine its purpose within the opposition ecosystem or risk fading into irrelevance. Otherwise, the next election will simply be another rerun of a losing formula—proof that the party remains stuck in the definition of insanity.

People’s Voice : Mental Institute on the move

If Singapore’s opposition scene were a stage, the People’s Voice (PV) would be its most theatrical act. Founded by Lim Tean, PV has positioned itself as the fiery, anti-establishment alternative, railing against the mainstream media, the PAP, and even other opposition parties. But beyond the bombast and social media soundbites, one has to ask: is PV really a political party, or just a “mental institute on the move”—loud, chaotic, and directionless?

From the start, PV has embraced a brand of populism rarely seen in Singaporean politics. While other opposition parties, like the Workers’ Party and the Progress Singapore Party, attempt to craft nuanced policies and appeal to the middle ground, PV thrives on outrage. Conspiracies, inflammatory rhetoric, and a near-total disregard for facts have become its trademarks. Whether it’s railing against vaccination policies or peddling economic fantasies, PV has built a reputation for saying what some want to hear—regardless of whether it makes sense.

Lim Tean himself is a walking contradiction. One moment, he declares himself a champion of the people; the next, he’s embroiled in legal troubles, from lawsuits to unpaid debts. His leadership style is less about building a credible political alternative and more about fueling personal grievances. The result? A party that feels more like a traveling circus of discontent rather than a serious electoral contender.

At its core, PV represents a fundamental misunderstanding of what it takes to be a viable opposition in Singapore. Shouting into the void may earn social media engagement, but it does not translate into electoral success. Without discipline, strategy, or coherent policies, PV risks being nothing more than an entertaining but irrelevant sideshow—a mental institute on the move, indeed.

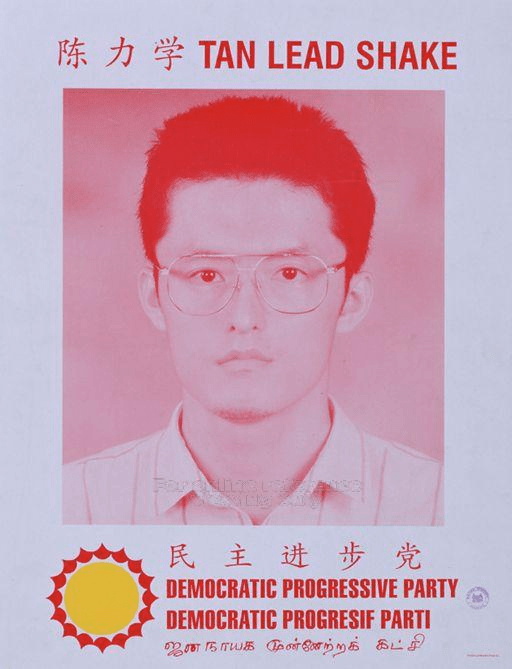

Democratic Progressive Party : Undefined, Unnoticed, and Uninspiring

If there were a ranking for Singapore’s most forgettable political parties, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) would be a strong contender for the top spot. Despite its long history—dating back to 1973 when it was first founded as the Singapore United Front—the party has remained largely undefined, unnoticed, and uninspiring. I often mistake this party for a petrol station, their symbols look way too similar.

For much of its existence, the DPP has struggled to carve out a distinct identity. Unlike the Workers’ Party, which has established strongholds, or even newer parties like the Progress Singapore Party, which have made headlines, the DPP remains politically invisible. It has contested in elections sporadically, often forming alliances with other opposition parties, yet never making a lasting impression.

Its leadership has also been unstable. The party has seen multiple changes in direction, with its most notable moment being a brief merger with the Singapore People’s Party (SPP) under Chiam See Tong. However, even this alliance failed to translate into electoral success. In recent years, the party has been virtually inactive, raising questions about whether it even functions as a political entity anymore.

In a political landscape where opposition parties must fight for relevance, the DPP stands out for doing the exact opposite. With no clear platform, no visible grassroots efforts, and no significant electoral presence, it remains an enigma—one that voters have little reason to take seriously. If the DPP continues on this path, its future might not just be uncertain—it might be nonexistent.

Singapore Peoples Party : A relic of the past

To be fair to them, there is a legacy behind the Singapore People’s Party (SPP). The party was once led by opposition pioneer Chiam See Tong, one of the most respected figures in Singapore’s political history. Under his leadership, SPP carried the hopes of opposition supporters, proving that non-PAP voices could have a place in Parliament. But riding on the coattails of a former politician is not a sustainable strategy, and that has been SPP’s fundamental problem.

Since Chiam’s departure from active politics, SPP has struggled to remain relevant. The party has not meaningfully evolved or adapted to Singapore’s changing political landscape. Instead, it continues to invoke Chiam’s name as its main source of legitimacy, as if nostalgia alone can translate into votes. Meanwhile, other opposition parties, particularly the Workers’ Party (WP) and Progress Singapore Party (PSP), have grown in stature by fielding fresh candidates and focusing on tangible issues.

SPP’s failure to adapt has led to its slow decline. Without a clear vision, strong leadership, or a compelling platform, it risks fading into complete obscurity. The opposition space in Singapore is more competitive than ever, and unless SPP reinvents itself, it will remain nothing more than a relic of the past—an artifact of Chiam See Tong’s legacy rather than a serious political force in its own right.

Singapore Democratic Alliance : A Forgotten Experiment

The Singapore Democratic Alliance (SDA) was once envisioned as a united front for opposition parties, a coalition that could challenge the PAP’s dominance by pooling resources and presenting a more coordinated opposition. Yet today, the SDA is little more than a political afterthought—a forgotten experiment in unity that never quite worked.

Initially formed in 2001 under the leadership of Chiam See Tong, the SDA brought together smaller opposition parties in hopes of avoiding three-cornered fights and increasing opposition representation in Parliament. However, internal conflicts soon unraveled the coalition. Chiam’s departure in 2011 left the SDA without a strong figurehead, and it has since faded into irrelevance, contesting only in Pasir Ris-Punggol GRC without making any real electoral impact.

Unlike the Workers’ Party or the Progress Singapore Party, which have built strong party identities, the SDA has struggled to define itself beyond being an alliance. With no clear ideological direction, limited engagement, and an outdated strategy, it feels like a relic of a time when opposition parties hoped that unity alone was enough to win votes.

If the SDA wants to remain relevant, it must do more than just show up at elections—it needs a vision, a purpose, and a reason for voters to take it seriously. Otherwise, it will continue to be what it is now: a political footnote in Singapore’s opposition history.

To note on the leader of the SDA, Desmond Lim, his lack of tack and grasp of the english language is one of his biggest flaws as a politician but as a human being, his honesty and determination has been one of his strongest points. Although the chances of his party winning are rather low. He deserves respect for his tenacity.